The banjo is a stringed instrument of African origin. The defining characteristic of the banjo is the use of a stretched membrane, originally an animal skin, to amplify the vibration of its strings. This arrangement creates the banjo's characteristic sound and differentiates it from instruments of European origin known in the Americas. The cultural history of the banjo and its place in the history of American race relations is profound. The instrument’s evolution and the music surrounding its development may be characterized a synthesis African and European traditions.

Africa and the Caribbean

The earliest documentation of banjo-type instruments is found in writings of 17th century travelers to Africa and the Americas. These writings document instruments in East Africa, North America, and the Caribbean that share common distinguishing characteristics: a gourd body topped with animal skin and with a fretless wooden neck. The number and composition of strings varied, but three or four strings were the general rule. Richard Jobson was the first to record the existence of such an instrument. While exploring the Gambra River in Africa in 1620 he described an instrument "...made of a great gourd and a neck, thereunto was fastened strings.” Adrien Dessalles in his 'Histoire des Antilles' published in 1678, records the use of a "banza" among the slave population of Martinique. Jamaican historian Edward Long describes the four stringed "merry whang" as a "rustic guitar" made from a "calabash" covered with a "a dried bladder, or skin." Similarly the "banshaw" was noted in St. Kitts and the "bangil" in Barbados.

The American Plantation

Thomas Jefferson in his Notes on Virginia, Vol. IV (1782 to 1786) states in a footnote, "The instrument proper to them is the Banjar, which they brought hither from Africa…." By the middle of the 18th century the banjo was so well known that it did not require a description. In 1749 the Pennsylvania Gazette carried a notice regarding a runaway slave named Scipio which, by way of description states that he "plays the banjo."

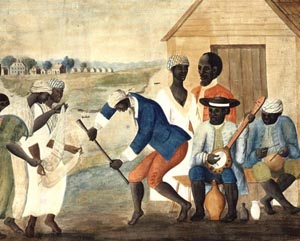

The sort of banjo Scipio may have played is documented in a Watercolor entitled "The Old Plantation" probably painted between 1790 and 1800. The composition features a banjo player accompanying several dancers in front of the slave quarters of a plantation. The banjo depicted has four strings, one of which is affixed to a tuning peg at the side of the neck. This short-scale string, called a "drone" string or “chanterelle” is a significant feature which is present on modern five string banjos. It allows the player to create the rhythms associated with the banjo. It is also a feature that sets the banjo apart from stringed instruments of Europe origin.

It was not long before the banjo crossed racial and social barriers. Philip Fithian, a tutor at Nominy Hall in Virginia, recorded in a diary entry dated February 4, 1774 "This evening, in the School-Room, which is below my Chamber, several Negroes & Ben, & Harry are playing on a banjo and dancing!" Fithian’s apparent chagrin at this scene is echoed by the writings of a contemporary, the Reverend Jonathan Boucher (no relation to banjo maker W.E. Boucher) who described the banjo as "in use, chiefly, if not entirely, among people of the lower classes." In the context of his writing, it is apparent that he includes lower-class whites among those who played the banjo. Fithian and Boucher's identification of the banjo with racial and class stereotypes has persisted subtly or overtly throughout the banjo's history. Despite this stigma, the banjo became driving force in one of America's first mass-cultural phenomena: the minstrel show.

The Minstrel Show

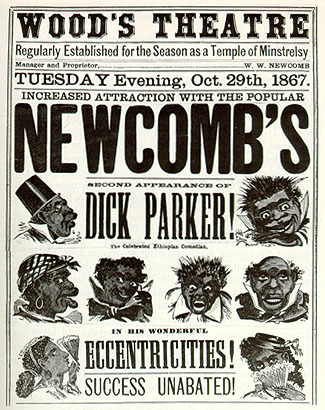

The form of entertainment that brought the banjo to the attention of the masses also represents a shameful exposition of overt racism in American popular culture. Blackface comedic and musical acts predated the minstrel show by several decades. Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice developed a stage persona called Jim Crow, a carefree, shiftless slave dressed in shabby clothes. Rice’s Jim Crow act was immediately successful and brought him acclaim during the 1820s and 1830s. Blackface performances were common between acts of plays and as circus acts. Minstrel shows were staged performances that included music, dance, and a variety of comedic performances. The stock-in-trade of the minstrel show was the parody of the lifestyles of slaves and free African Americans. Stock characters of the minstrel show included Jim Crow, Mr. Tambo (a joyous musician), and Zip Coon (a free black attempting to put on airs in imitation of white gentry). Skits and satirical speeches were delivered in stylized black dialect. These savage caricatures of the lives of African Americans were met with overwhelming approbation among white audiences.

|

|

|

Racial stereotypes depicted in a |

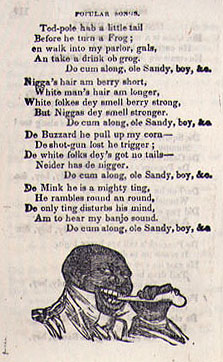

Racist lyrics from a song from the minstrel period. |

The staging of Dan Emmett's Virginia Minstrels at New York's Bowery Amphitheatre in 1843 marks the beginning of the full-blown minstrel show in which the entire cast “blackened up.” Emmett’s core group included Emmett on fiddle, Billy Whitlock on banjo, a tambourine player, and a bones player. These instruments constituted the basic minstrel ensemble and this formula was imitated by professional and amateur musicians alike.

The overwhelming popularity of the minstrel show created a new class of professional banjoists and a demand for high-quality instruments. By the 1840s gourd-bodied banjos had generally given way to construction of a drum-like sound chamber. This new arrangement offered two major advantages: The size of the drum shell or was not limited to the size of a natural gourd (eight inches, or so in diameter), and the tension on the drum head could be adjusted to counteract the effects of humidity on the natural skin. The banjo of the minstrel stage featured a range of head diameters, generally of 12 to 13 inches and five gut strings, one of which was a short-scale drone string, and a fretless neck.

To meet the new demand furniture makers, drum makers, guitar manufacturers and others got into the business of making banjos. Gradually luthiers specializing in banjo production emerged. One of the most prominent of these was William Esperance Boucher (1822-1899). Boucher’s Baltimore, Maryland firm sold drums, violins and guitars. Many of his banjos featured an elegant scroll peghead and decorative profiling of the drone-string side of the neck. Boucher set a high standard of quality and aesthetics. His banjos were popular among professional musicians. Another banjo maker of note was British-born guitar maker James Ashborn whose Connecticut factory produced banjos in the late 1840s. His unadorned and practical instruments were common on the minstrel stage and set a high standard for professional instruments. Ashborn is also credited with producing some of the first banjos featuring fretted necks.

Jazz

Between 1890 to 1920 the popularity of the minstrel music was eclipsed by early jazz forms, such as ragtime. The popularity of the banjo as a parlor instrument fell into decline. The features which made the banjo ideal for minstrel music became liabilities when attempting the complex chord structures of jazz. These include a reliance on “open” tunings (strings tuned to a major chord) and the drone string which plays at a constant pitch.

|

|

Celestin's Original Tuxedo Jazz Orchestra (circa 1926)featured the four-string jazz banjoist Narvin Kimball |

New configurations of the banjo were invented to meet this new musical challenge. The popularity of the mandolin was concurrent with the banjo’s popularity in the latter 19th century. The mandolin’s tuning arrangement (in fifths as in a violin) is inherently more versatile in that it allows performers to play any chord or in any key without retuning or using a capo. Banjo-mandolin hybrids emerged, resulting ultimately in banjos suitable to jazz playing. The availability of metal strings also gave the banjo more volume and facilitated this transformation. Ultimately two types of four string banjos emerged in the jazz period, plectrum and tenor banjos. Plectrum banjos are similar to five-string banjos of the late minstrel period, but without the short-scale drone string. Tenor banjos are an outgrowth of the mandolin banjo, featuring scale length somewhat shorter than the plectrum banjo and strings tuned in intervals of fifths.

The decline of popularity of the five string banjo is evident from the history of theGibson Company of Kalamazoo, Michigan. Gibson was the preeminent mandolin manufacturing company of its day and began marketing banjos for the jazz market in 1918. Gibson sold four string banjos and every other sort of banjo hybrid instrument but did not produce five string banjos for the first several years of production. The Gibson company introduced the "Mastertone" which by the 1930s incorporated it's most notable innovation, a heavy cast-bronze tone ring. This, in combination with a tone chamber backed by an improved resonator, created an instrument of impressive volume and tonal clarity. The Gibson company is also responsible for the invention of the truss rod which, when embedded in a banjo neck, counteracts string tension and allows for necks of thinner construction. Thus, by the mid 1930s the modern banjo reached a state of development which has remained essentially unchanged.

Styles of Play

There is no detailed record of how early banjos were played. The first banjo tutors published in response to the popularity of minstrelsy. One such tutor is Briggs Banjo Instructor published in 1855. The method for the right hand described in Briggs’ tutor likely represents an unbroken tradition from the early banjo of the plantation to his day. It requires the player to strike the strings with the fingernails using downward movement. This basic right hand movement has had various names according to region and time period. Modern players use the terms “clawhammer” and “frailing” among others.

The Parlor

By the late 19th century the banjo had become a popular parlor instrument. A new class of hobbiest banjo players emerged, including middle- and upper-middle-class women. Banjo manufacturers, eager to supply this market began to produce ornate instruments of more delicate proportions that included ebony fingerboards with engraved mother of pearl and necks with carved floral and acanthus leaf patterns.

|

|

The Barnard Banjo Club, ca. 1897 |

Buckley's New Banjo Method published in 1860 offered the players instruction in “classical” banjo. The classical style featured right hand technique similar to classical guitar in which the fingertips pluck the strings upward.

Dixieland

Four string banjos were developed to respond to the popularity of jazz musicin the early 1900s. Tenor banjos and plectrum banjos became standard instruments in jazz ensembles and remained popular until they were supplanted by the electric guitar. Jazz banjos are played with a plectrum, like the modern “flat pick.” The use of banjos in jazz was curtailed by the advent of electric guitars and relegated to early jazz forms, such as Dixieland. Virtuoso plectrum and tenor players were frequently seen on the Vaudeville stage.

Rural String Band

While 19th century northern urbanites played their dandified pearl-inlayed banjos, and unbroken tradition of finger styles and frailing styles continued on in rural areas of the South and elsewhere. These traditions probably go back as far as the colonial period and it can be argued that in these areas, the transfer of banjo playing from black musicians to white musicians was direct and that isolation kept the playing styles relatively free of interpretation. In rural communities, fiddle and banjo--and sometimes banjo alone--were the mainstay of rural dance accompaniment.

|

|

Charlie Poole, pioneer of the rural string band. (1892-1931) |

From the end of the minstrel period to the advent of the recording industry, five string banjo traditions were kept alive by rural banjo players. Rural string bands recorded in the 20S and 30S played a mix of traditional fiddle tunes, ballads, country blues, and ragtime-influenced compositions. This new admixture proved a popular and created a new genre of “hillbilly” offerings. The predominant style of banjo playing in these recordings was essentially the minstrel “knock down” style, though two-finger and early three-finger picking styles were also recorded.

Bluegrass

By the 1930s record labels, such as Brunswick sought out rural talent recording string bands and individual talent. What emerges form these early recordings is a mosaic of regional styles. Notable among these was banjoist Doc Boggs who employed eccentric banjo tunings and a blues influenced fingerstyle. This contrasts sharply with the straight-ahead frailing style of artists such as Hobart Smith and Clarence Ashley.

Among the successful recording artists of the 1930s was a young man named Bill Monroe who recorded as a duet with his brother Charlie. In the 1940s Bill Monroe remade the rural string band format into the driving sound, later called "Bluegrass" in honor of Monroe's native Kentucky.

|

|

Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, |

Monroe was a master mandolin player and surrounded himself with the best talent of his day. Early incarnations of Monroe's Bluegrass Boys included banjoist Dave "Stringbean" Akeman who played in the frailing style. Monroe favored having a banjo in the ensemble, but even the talented Akeman could not keep pace with Monroe's pyrotechnic mandolin playing. Akeman was eventually sacked. One of Monroe’s sidemen happened to hear the playing of a young and shy North Carolinian, Earl Scruggs, and encouraged Monroe to audition him. Monroe was skeptical but agreed to the audition. Scruggs skill and style impressed Monroe and he was quickly hired.

Earl Scruggs’ style is based on rapid picking of the thumb, index finger and middle finger of the right hand and employs metal picks for the fingers and a plastic thumb pick. Scruggs had predecessors in the three-finger style and may have inherited some concepts from artists such as “Snuffy” Jenkins but Scruggs’ sublime mastery of the style set him apart and completed the Bluegrass formula.

Melodic Style

Variations on Earl's pioneering work soon followed. The next two decades saw a new generation of bluegrass players, some of them born and bred in the suburbs and the city. Bill Keith was one such player who pioneered the "melodic" style of play. Melodic style differs from scruggs style in that it is less dependent on roll patterns and seeks the melody more directly, particularly on melody-intensive numbers such as fiddle tunes. Keith played with Monroe's Bluegrass Boys and Monroe noted with satisfaction that Keith had accomplished what he suspected that the banjo was capable of (i.e., produce a complex melody line note for note).

A survey of modern banjo playing would not be complete without mention of the influence of Bela Fleck. At an early age Fleck was a master of Scruggs and melodic styles. He later pioneered jazz styles for five string banjo. Fleck cites jazz pianist Chick Corea as a major influence.

Folk Boom

The folk boom of the 50s and 60s brought old time players to the attention of young players. Many fine players were brought out of retirement and given a second musical career, incuding Doc Boggs, Clarence "Tom" Ashley and Hobart Smith. Simultaneously modern folk styles of banjo playing emerged, influenced in large part by Pete Seeger who produced solo albums and performed wtih musical groups such as the Almanac Singers and the Weavers. Groups such as the Kingston Trio featured banjo played in a semi-strumming style designed more as an accompanyment to singing than as a solo style.

|

|

Newport Folk Festival album cover |

The Newport Festival recordings of the 1960s were notable in that old time players, such as Ashley shared the stage with inheritors of the earlier styles, such as Mike Seeger of the New Lost City Ramblers. Ashley's collaboration with guitarist Doc Watson and fiddler Fred Price in these recordings presented to a new generation the authentic rural string band style.